Battling Anti-Union Political Foes

February 24, 2025

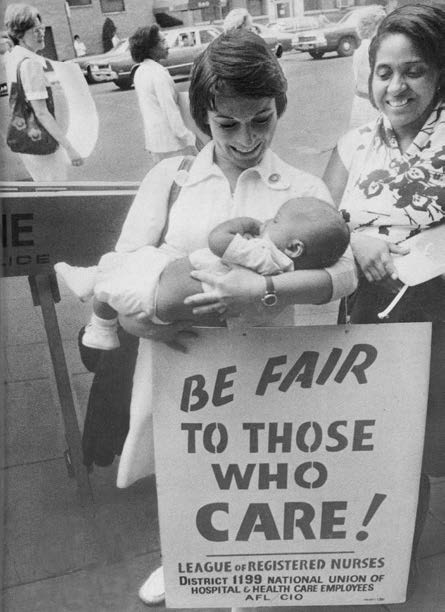

1199 has won gains in hostile environments.

After defying the odds by organizing poor hospital workers in the late 1950s, the Union felt ready to tackle any obstacle in its path. Not only had it emboldened its members, but it had also roused the progressive community.

Its support came not just from liberals and moderates like Eleanor Roosevelt, widow of former President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, but from such militant activists as Malcolm X. Not long before his 1965 assassination, the Black Muslim leader said, “1199 was not afraid of upsetting the status quo or the apple cart of those people who are running City Hall or sitting in Albany or sitting in the White House.”

The Union’s most significant victory in the 1960s was pressuring the New York State legislature to pass a bill extending collective bargaining rights to New York City voluntary hospitals, and then getting Republican Governor Nelson Rockefeller to sign it.

The 1970s posed new political challenges. Even though 1199 had ratified a two-year contract granting wage increases of 7.5 percent in June 1972, then President Richard Nixon’s Pay Board—ostensibly to curb inflation—limited increases to 5.5 percent in the second year of the pact.

On Nov. 5, 1973, some 30,000 workers walked out of 48 voluntary hospitals. At the time, it was the largest strike ever in the healthcare industry. Federal officials originally refused to negotiate. But on Nov. 12, the council offered a compromise of six percent.

Although the increase fell short, members voted overwhelmingly to end the strike. The members had won more than a small wage increase. They boasted that they were the only workers in the nation to strike against a grossly unfair policy that curbed wages while leaving corporate profits intact.

1199 organizing director Elliott Godoff said at the time, “One of 1199’s primary tasks was to help members learn how to assert their rights not only on the job, but also as citizens of their community and their country.”

Mindful of the need to meet the challenges of an increasingly difficult organizing environment, Leon Davis spoke at the 1978 convention of the Service Employees International Union (SEIU) and raised the prospect of a joint effort to organize all health care workers into one union.

Internal divisions within 1199 during the first half of the 1980s derailed merger plans and led to other setbacks. But the victory of the reformist Save Our Union (SAO) slate in 1986 returned the Union to its former progressive path.

One of SAO’s first campaigns in 1987 was the organization of home care workers—a vital sector of the healthcare workforce that other unions were reluctant to organize. The leadership drew comparisons between the plight of those workers —primarily women of color—and that of impoverished voluntary hospital workers thirty years earlier.

In this “Crusade for Justice,” the Union once again called on its allies, among them representatives of the women’s movement, Manhattan Borough President David Dinkins, New York’s Cardinal John O’Connor and the Rev. Jesse Jackson.

The next year, Jackson mounted a campaign for the U.S. presidency. 1199, in whose office the campaign was headquartered, helped Jackson carry New York City in the Democratic primaries. One year later, 1199 worked with young Jackson campaign activists, among them former Mayor Bill de Blasio and Patrick Gaspard, former 1199 officer and President Barack Obama’s political director, to elect the city’s first Black mayor, David Dinkins.

In 1998, 1199 became a more formidable force within labor and the progressive movement when it finally merged with SEIU and several SEIU locals. By the close of the decade, 1199 reported that its work had forced Albany to back down on more than $11 billion in proposed Medicaid cuts.

In 1999, the Union and the Greater New York Hospital Association (GNYHA) formed the Health Care Education Project (HEP). The partnership developed into New York’s most effective advocate for quality, affordable healthcare.

“The Affordable Care Act would not have passed without the work of HEP,” declares Dennis Rivera, former president of 1199, on HEP’s website. Former President Barack Obama officials have praised HEP and1199 for its work in helping to win passage of the ACA in the face of stubborn Republican opposition.

The ACA, although falling short of full universal coverage, has cut the uninsured rate by more than half. It also has expanded Medicaid and prevented insurance plans from denying coverage or charging higher premiums based on preexisting health conditions. Through the work of HEP, and in state capitals throughout 1199’s regions, members have been on the frontlines defending and extending health care and a better life for all in both friendly and hostile political environments. During the next four years, members will continue to point their collective power in the direction of preserving and expanding affordable healthcare for the most vulnerable in society.