How BREAD AND ROSES Helped Build 1199

October 17, 2019

Innovative cultural program enriched members’ lives.

1199 was already highly regarded for having lifted thousands of hospital workers out of poverty and providing them with world-class benefits. Foner and the leadership of 1199 firmly believed that economic gains to meet the material needs of members should be supplemented by cultural programs to enrich members’ lives. The birth of the Bread and Roses cultural program further cemented the Union’s reputation as an arts pioneer as well as a social justice champion.

“Art should be a right for everyone, not a privilege for a few,” declared 1199 Pres. Leon Davis. Thus, the name Bread (wages) and Roses (culture), the rallying cry of 1912 striking textile workers—mostly immigrant women and girls—in Lawrence, MA.

In its first six years, Bread and Roses raised about $2 million to fund its programs. But those funds could not have been obtained and the program come into existence without the participation and support of a committed, mobilized membership.

Before launching the program, Foner spoke at delegates’ meetings to ask for volunteers. Some four hundred members stepped forward.

A highlight of its first year’s activities was its 1979 Labor Day Street Fair, held on 42nd Street near the Union’s New York City headquarters. The Labor Day holiday was chosen to underscore the connection between bread and roses.

The holiday also traces its origins to the struggle of striking workers. In 1894, tens of thousands of Pullman car workers walked off the job after the company fired workers who complained when the Pullman company lowered their wages. During the militant strike, led by socialist firebrand Eugene Debs, some 30 workers were murdered by Pullman goons.

“ A GOOD UNION DOESN’T HAVE TO BE DULL.”

– Moe Foner, founder, Bread and Roses

During the crisis, President Grover Cleveland sided with Pullman against the strikers. But fearful of losing labor support, Cleveland signed a bill into law declaring Labor Day a national holiday. Even before the national holiday, unions had set aside the first Monday in September to celebrate labor’s contributions and to press for further gains. New York City held its first Labor Day parade and picnic on Sept. 5, 1882.

By 1979, the New York City celebration had fallen out of favor. Bread and Roses sought to fill that void. The fair was broadly advertised in the media and with posters, buttons, fliers, and street banners. The publicity bore fruit, as some 75,000 New Yorkers flocked to the event. Fairgoers were treated to free labor films, a variety of live music, comedians, jugglers, magicians, dancers, and the well-known Bread and Puppet Theater.

Dozens of 1199 members took turns working the booths. Members offered free blood pressure tests and nutrition counseling. Members of other unions also exhibited their skills such as sewing and cutting by clothing and textile unions, cake decorating by union bakers, subway and bus tours by transport workers, and various building skills by members of the Building and Construction Trades Council. A group of women of color who were campaigning for entry into building trades unions constructed the frame of a house on the street while speaking to fairgoers about their campaign.

During 1979 alone, Bread and Roses produced a Harry Belafonte concert at Lincoln Center, the artist’s first appearance in New York City in 18 years; a UNICEF “Year of the Child” exhibit; a photo exhibit of textile workers and another about working Americans; a Latin Cultural Festival; Theater in the Hospitals; Theater 1199 starring Ossie Davis and Ruby Dee; “I Just Wanted Someone to Know,” a one-act musical about working women; a Bread and Roses poster; and a series of interviews on the legacy of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

“Patient Care: The Health Care Employee’s Responsibility” was a Bread and Roses conference that drew a wide and appreciative audience of members, management, and patient advocates. A highlight of the event was the testimony of a paraplegic Thomas Clancy. He said: “The person who touches you at the right time, holds your hand, or says something insignificant but magical... These images are implanted in your mind forever.”

Such conferences, lectures, and cultural events strengthened members’ involvement as well as their identification and commitment to the Union. The arts and education programs also distinguished 1199 as a cultural leader in the city. Artists were eager to associate themselves with an organization that modeled social and economic justice.

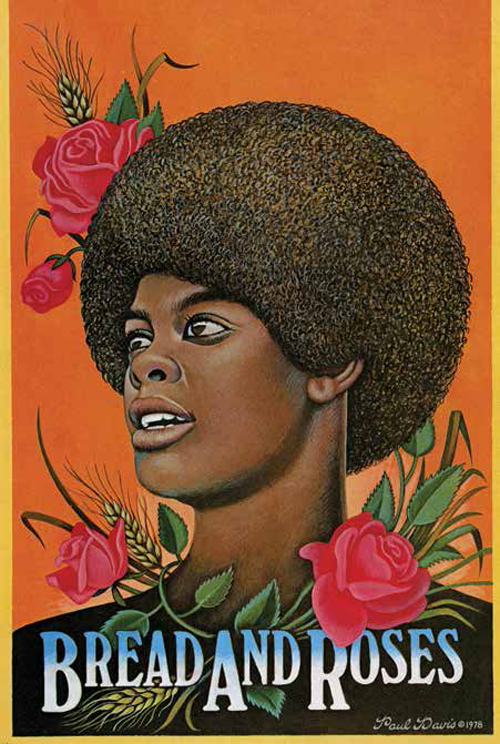

The 1199 Gallery, the only art gallery in a union headquarters, soon gained go-to status. Photo and art exhibits of working Americans frequently lined the walls. So popular was the gallery that it remained open on weekends, often staffed by 1199 retirees. A Bread and Roses poster by leading graphic artist Paul Davis was circulated widely in union halls and public venues and printed in national publications.

The success of Theater 1199 and Theater in the Hospitals inspired what would become one of Bread and Roses’ greatest achievements, “Take Care,” a traveling musical production whose sketches and songs were derived from material collected in workshops with hospital workers. Workers and critics praised the work for its honest portrayal of hospital staff, particularly service workers who seldom were depicted in popular culture. The production toured 45 hospitals in New York alone. It also made an 11-state tour in which it was seen by more than 35,000 hospital workers.

Bread and Roses also had smashing success with its “Images of Labor” poster series, in which famous labor quotes were paired with works by prominent artists. In four years, “Images of Labor” was seen by more than half a million people, making it the most successful exhibit of art with a labor theme in our nation’s history.

The art was later assembled into a book published by Pilgrim Press. The book’s preface was written by Joan Mondale, wife of former Vice president Walter Mondale. The poster series continued with “Women of Hope.” Some 85,000 sets were sold.

Today, some of the posters still hang on the walls of unions and other organizations.

The Bread and Roses program continues today. Its success through the years bear out Foner’s assertion, “A good union doesn’t have to be dull.”

1199 Magazine | September / October 2019