ON FRONTLINES OF BLACK FREEDOM STRUGGLE

February 27, 2020

1199 was one of the first unions to celebrate Negro History Week

In the 1930s, 1199 launched a successful campaign in Harlem to pressure drugstores to hire African American pharmacists and promote Black porters to the position of sodamen. One of those porters, Theodore Mitchell, became the Union’s first African- American officer.

In 1949, 1199 Pres. Leon Davis credited Harlem members with saving the Union. During “red scare” attacks by the federal government and raids by an opposing union, the North Harlem Pharmaceutical Association, led by 1199er Howard Reckling, shut down a hundred drugstores to prevent them from being certified by the hostile union. Reckling went on to lead the National Pharmaceutical Association.

He and other Harlem pharmacists in the same period hid Davis and 1199 Treasurer Eddie Ayash at the Harlem YMCA to delay the serving of a subpoena.

The African American pharmacists refused to show up for work until the owners signed with 1199.

1199 declared that real progress could not be achieved for all without eliminating the whole vicious system of white supremacy. To that end, a centerpiece of 1199’s organization and mobilization has always been underscoring the connection between union rights and civil rights. To this day, members are encouraged to participate in political and civic activities and contribute to labor and social justice campaigns. In 1960, members and staff picketed Woolworth’s stores in New York City to protest lunch-counter segregation at the chain’s southern stores. Others participated in the historic Freedom Rides.

Culture was also central. Activist artists Ossie Davis and Ruby Dee often performed during Negro History Week celebrations. They and fellow artists dramatized civil rights events, such as the Montgomery bus boycott at which Rosa Parks and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. came to prominence Dr. King was a frequent visitor to 1199 headquarters. Few communicated as brilliantly the unbreakable ties between the economic and social struggles of working people. He said of 1199’s historic 1959 hospital strike, “It is more than a fight for union rights, it is a fight for human rights and human dignity.”

Dr. King stood with 1199 during the strikes for recognition at Beth El (now Brookdale) and Manhattan Eye and Ear hospitals in 1962. That campaign led to collective bargaining rights for New York City voluntary hospital workers. A victory rally just days after the settlement reflected 1199’s influence and foreshadowed the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom the next year.

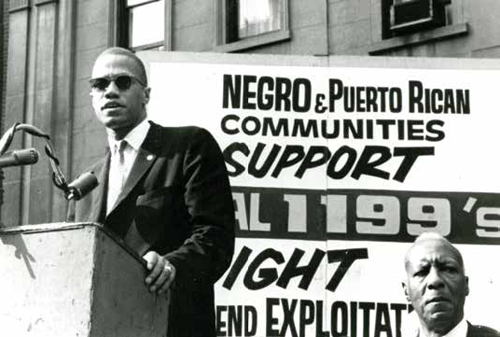

Among the organizers of the rally were Bayard Rustin, who with labor titan A. Phillip Randolph, was a principal architect of the 1963 March. Randolph and Roy Wilkins, leader of the NAACP and a 1963 March speaker, addressed the 1199 rally. Dr. King was a scheduled speaker but was unable to attend. Another speaker, Malcolm Union-chartered train. They saw firsthand that their Union demands were in step with those of the Civil-Rights Movement. Members returned from the March committed to apply the lessons of history by making history.

Their immediate task was to win collective bargaining rights for all voluntary hospital workers in New York State with a campaign called “Operation First-Class Citizenship.” The first target was Lawrence Hospital in Bronxville, NY. The national and local civil rights leaders who aided 1199 in New York City also assisted the Lawrence campaign.

After a 55-day strike and on the eve of a planned civil rights march, the legislature agreed to extend collective bargaining to the entire state. Though Union wouldn’t win a contract at Lawrence for another 37 years, workers persisted in the struggle for justice at the hospital, with leaders like sisters Marion and Mary Beavers walking Lawrence picket lines in 1965 and again in 2002, as leaders of the contract campaign.

Throughout the turbulent decades of the 1960s, the members joined Dr. King and other civil rights leaders at marches in the South, including the 1965 voting-rights march in Selma, Alabama. 1199’s blue and white paper caps became a much-sought-after symbol of justice and equality.

The 1960s ended with a highly publicized protracted fight in the Deep South. In 1969, some 450 workers at the Medical College Hospital of the University of South Carolina (MCH) and the smaller Charleston County Hospital struck for three months for 1199 recognition and protection. The strikers, led by MCH nurse’s aide Mary Moultrie, were all low-paid African Americans and 90 percent were women.

They were inspired by the presence of Coretta Scott King, the honorary chairperson of the Union’s national organizing campaign. The workers never won Union recognition, but the struggle led to significant changes in Charleston and the campaign helped 1199 establish a beachhead in the South. One year later, the “Union Power. Soul Power” campaign organized nearly 6,000 workers at six hospitals in Baltimore.

1199 has remained faithful to its progressive roots, hewing to Dr. King’s example with his teachings as its North Star. On March 10, 1968, less than a month before his assassination, Dr. King addressed 1199’s annual “Salute to Freedom” celebration and declared: “I’m often disenchanted with some segments of the power structure of the labor movement. But in these moments of disenchantment, I begin to think of Unions like Local 1199 and it gives me renewed courage and vigor to carry on.” Dr. King added, “I’ve been with 1199 so many times in the past that I consider myself a fellow 1199er.”

1199ers returned from Washington in 1963 determined to make history and have done so, leading 1199 in the struggles for equality, peace, justice, solidarity and more. Lillian Hicks was a student nurse at Atlanta’s Grady Hospital when Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was born there. At the time of Dr. King’s death, she was an 1199 delegate and LPN at New York City’s Hospital for Joint Diseases. She reflected the sentiments of 1199 when she said, “Knowing Dr. King has made me more determined to be a better human being.”

- 1199 Magazine: January / February 2020