How Will Automation, AI Impact Healthcare Employment?

January 30, 2019

by Jacqueline LaPointe, Revcycle Intelligence

Healthcare employment will have low exposure to automation in the next decade despite the increased use of artificial intelligence to replace some tasks, experts predict.

January 30, 2019 - Increased use of automation and artificial intelligence is slated to replace millions of jobs and tasks in the near future. However, healthcare employment is relatively safe from automation, according to a new report from the Brookings Metropolitan Policy Program.

The report, titled Automation and Artificial Intelligence: How machines are affecting people and places, looks back at how automation impacted the workforce from the 1980s to 2016 and offers projections on how new automation and artificial intelligence (AI) tools will affect the economy by 2030.

“The next phase of automation, increasingly involving AI, seems like it should be manageable in the aggregate labor market, though there are many sources of uncertainty,” Mark Muro, Senior Fellow and lead author of the report, stated in a press release. “With that said, the potential effects will vary significantly across occupations, regions, and demographic groups, which means that policymakers, industry, and society as a whole needs to focus much more than they are on ensuring the coming transitions will work for all of those affected.”

Muro and his co-authors Robert Maxim and Jacob Whiton found that only approximately one-quarter of US jobs (36 million positions in 2016) are at an elevated risk of automation in the coming decade.

Meanwhile, about 36 percent of US employment, or 52 million jobs in 2016, face medium exposure by 2030, and the remaining 39 percent (57 million jobs in 2016) will experience low exposure.

The healthcare workforce sits in the medium to low exposure buckets, the report shows.

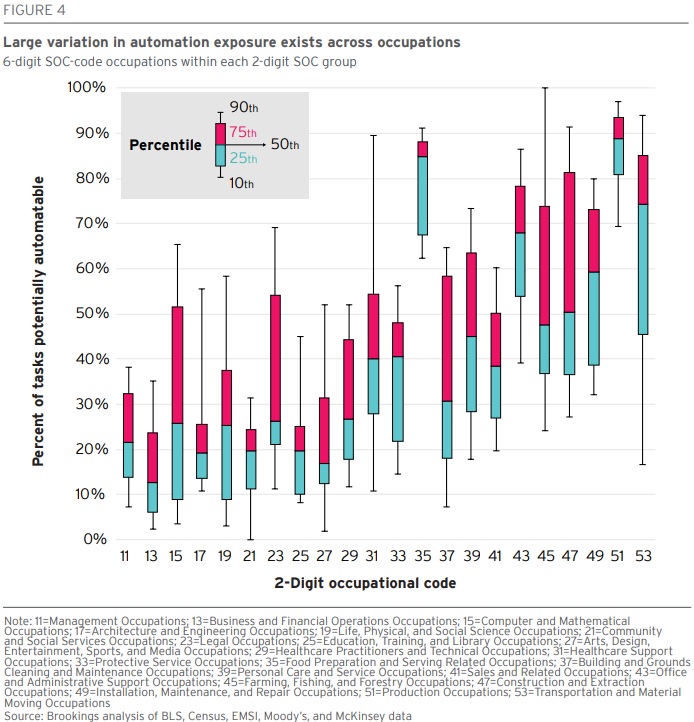

“Regardless of whether technological reality will keep up with technological possibility, the pattern of automatability is clear,” Muro et al. write. “Occupations in complex, creative, and social fields like management, business and finance, science and technology (computer, math, physical and life sciences, architecture, and engineering), law, education, arts, media, entertainment, healthcare, and social and community services (those to the left of the bar chart) have among the lowest automation potential across the workforce.”

For example, home health aides only have an eight percent automation potential by 2030, while registered nurses have a 29 percent automation potential and medical assistants have a 54 percent automation potential.

Additionally, healthcare practitioners and technical occupations have a 33 percent current-task automation potential and healthcare support occupations have a 49 percent potential.

In contrast, jobs that are in “more cut-and-dried activity areas” such as office administration, agriculture, construction and extraction, maintenance and repair, production, transportation, and food services will experience the highest automation potential.

In the middle are protective services, building and ground maintenance, and personal services, the report states.

Despite different levels of automation potential, researchers emphasize that no occupation will be unaffected by the adoption of automation and artificial intelligence. Routine tasks will be the most vulnerable to automation in the next decade.

“Near-future automation potential will be highest for roles that now pay the lowest wages,” the report states. “Likewise, the average automation potential of occupations requiring a bachelor’s degree runs to just 24 percent, less than half the 55 percent task exposure faced by roles requiring less than a bachelor’s degree.”

“Given this, better-educated, higher-paid earners for the most part will continue to face lower automation threats based on current task content—though that could change as AI begins to put pressure on some higher-wage ‘non-routine’ jobs.”

Automation risk will be the most disruptive in the American Heartland, so Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Ohio, Nebraska, North Dakota, South Dakota, and Wisconsin, the report also stated.

“Overall, the 19 states that the Walton Family Foundation labels as the American Heartland have an average employment-weighted automation potential of 47 percent of current tasks, compared with 45 percent in the rest of the country,” researchers write. “Much of this exposure reflects Heartland states’ longstanding and continued specialization in manufacturing and agricultural industries.”

Similarly, smaller, more rural communities will also see significantly more automation exposure and task replacement compared to urban areas.

In addition, the report states that men, young workers, and under-represented communities have greater automation exposure.

Automation and artificial intelligence will impact the US workforce in the next decade. But the potential loss or task replacement for some occupation isn’t as dire as some say.

“Technologists at first issued scary dystopian alarms about the power of automation, including artificial intelligence, to destroy work,” researchers write. “Now, the discourse appears to be arriving at a more balanced story that suggests that while the robots are coming they will bring neither an apocalypse nor utopia, but instead both benefits and stress alike.”

Federal, state, and local policymakers, business, educators, and civil society have the power to ensure automation and artificial intelligence maximize productivity while mitigating negative labor market effects, they add.

“In this vein, the nation needs to commit to deep-set educational changes, new efforts to help workers and communities adjust to change, and a more serious commitment to reducing hardships for those who are struggling,” the report concludes. “If the nation can commit to its people in this way, a future full of machines will seem much more tolerable.”