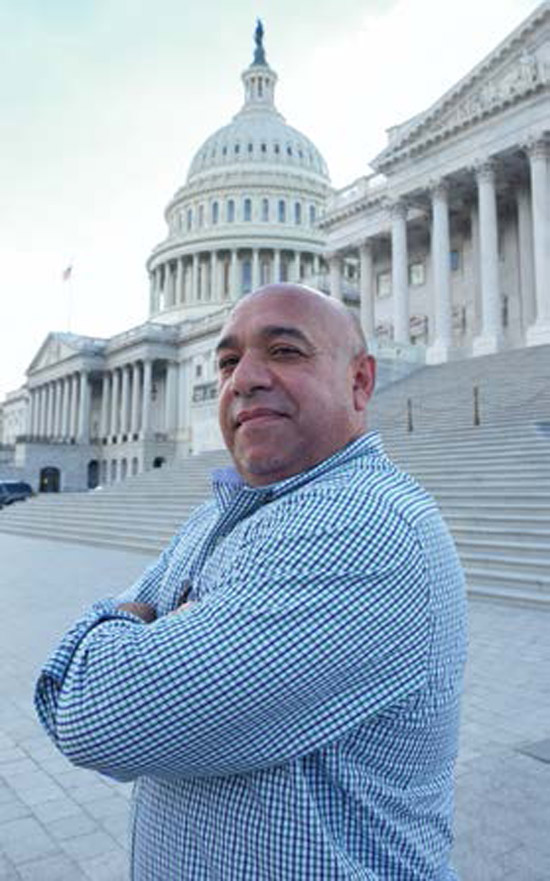

Our Delegates: Luis Santiago, HIV/AIDS counsellor at Jamaica Hospital in New York City

November 14, 2017

“Management wanted my team, who were not unionized, to go work in the hospital laundry. I knew those laundry jobs were union positions and I didn’t want to cross the line. So I led the team right through the hospital and out the other side. We went and got a bite to eat,” he recalls.

After that show of solidarity, Santiago worked to unionize his own team. Management asserted that a grant-funded team could not join 1199, but Santiago was pretty sure that wasn’t true and sought an 1199 organizer to find out.

Santiago’s efforts changed his supervisor’s attitude toward him, he says.

“I knew I couldn’t get caught up in how she was viewing me. I had to move forward and do what was right for me and my family,” he recalls. Santiago was paying $200 a month for health insurance for himself, his wife and his son—not including deductibles.

“I didn’t have any job security either,” he adds.

After almost 12 years of persistent, low-key organizing, Santiago’s team won a 2008 vote for 1199 representation. Two years later, he became a delegate.

“People say I should have been a politician. I’m always looking to help. That is why I became a counsellor. It is really important to me to educate my brothers and sisters and inform them of their rights,” he says with a smile.

“It feels great when I find something in the contract that the supervisors and administrators didn’t know. To a certain extent delegates are like lawyers,” he affirms.

Santiago also wants to make sure community residents’ concerns are heard and tries to educate members about the importance of getting involved in politics.

“A lot of only people think of the union in terms of benefits,” says Santiago, pointing out the difficulty of winning good contracts if healthcare funding is cut.

Santiago’s son, Luis, Jr. is studying to be an anesthesiologist.

“I try to set an example for him,” says Santiago, going on to tell the story of resolving a black mold infestation in Luis, Jr.’s Brooklyn middle school. Santiago got the NYC Department of Education to tackle the problem quickly by involving local politicians and the media. In the recent New York City Council primary races, Santiago spent a month canvassing in Queens for Francisco Moya. At press time, Luis was headed to a Washington, D.C. Lobby Day to meet with elected officials about maintaining Medicaid funding and other programs our healthcare system depends on.

“I try to be a voice for my community,” he says. “Minorities don’t come out and vote enough. People don’t always realize thatimpact that voting has on their own community. When people don’t want to vote, I tell them frankly:

‘Don’t complain when you don’t get what you’re looking for in terms of housing, education, jobs and medical cover for senior citizens.’”

Last year, Santiago took several turns as a Weekend Warrior, campaigning in Pennsylvania for Hillary Clinton. He recalls the election results with wistful determination.

“I think a lot of us were disappointed, especially when we put in all the hours of hard work. But we need to continue the fight despite who is in office,” affirms Santiago, who clearly has no intention of giving up the fight for working people.

“I joined the union for the simple reason that we need people to speak up for our rights under the contract,” he says. “People have fought hard to make 1199 what it is. I want to get as many people involved as I can.”